Photo: Gerd Altmann by Pixabay.

Technocracy and the Third World War. An Essay Concerning the Question:

What Are the Most Effective Mechanisms of Power in the Today’s Global Society ? Part I

Many people think that the current world crisis is a result of the effects of a virus. However, what we are experiencing today is far more comprehensive—it is about a fundamental reset of society on a global scale. Above all, the current crisis is a power struggle and has many characteristics of a war. But what kind of war? Who started it? Is it a battle between nations and, if so, what are they fighting for ?

This text was first published on 19.04.2021 at <https://www.transformation20-25.net/> under the following URL: <https://www.transformation20-25.net/post/teknokratiet>. License: Kathrine Elizabeth Lorena Johansson © transformation20-25.net

First of all, we must understand that we have reached a new stage in the evolution of warfare. The initial stages of this war have shown that it is taking shape differently to former world wars.

War is about power and the control of resources. It is about using methods that overstep the rights of individuals in order to attain power.

Each world war has had different characteristics. In general, each war incorporates the knowledge, technology and communication technologies characteristic of its own historical period. Today’s war is thus different to former wars. Over time, there has been a continual move away from physical combat at close quarters to combat with a steadily expanding geographic range and ever more devastating weapons. World War I was characterised by new flight and bombing technologies, trench warfare and the use of chemical weapons (including trials with vaccines using field soldiers at the field hospitals in Germany). World War II led to a more advanced and industrialised war machine, strongly influenced by an ideology of ‘scientific management’ and was characterised by organized transportation, organized death camps, advanced (unethical) medical research and experimentation with the atom bomb in Japan.

Today’s war has shifted further away from the physically tangible dimension, into more virtual realms.

War has become less visible, but more universal in its reach. This war involves the whole world at one and the same time.

„Spyros Koukoulomatis Technocrat“ by Yannis Zannias Creative Commons.

The overall goal, however, remains the same: gaining power and control over populations and resources. In this article I attempt to outline the characteristics of the war we are presently experiencing and probe more deeply into the following question: How is it possible that so many nations and authorities seem to be following the same script, in spite of a very low level of scientific credibility and logical coherence in both the foundational explanations and strategies of action pursued by both Danish and foreign governments? To reach a greater understanding of the situation, we further ask: How do we determine the source of the power and resources that make such a global coup d’etat possible? In this article, I retain a special focus on the West and on technocracy per se.

Communism, liberalism or a whole new concept?

Many people have discussed the silent war we are experiencing and how it seems to be an attempt to drive modern nations into a kind of communism with the state gaining total power, enabling it to systemically control of the lives of citizens in a brutal and repressive way. In the past, we have seen variations of this dynamic in communist states in Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, or more harshly in North Korea and China. From a realistic point of view, both socialism (Karl Marx) and liberalism (John Locke, Adam Smith) represent outdated theories relating to a world that existed more than one hundred years ago. One must wonder whether countries that still adhere to a communist ideology, such as China today, may also be moving towards an entirely new condition—not only in the way the country integrates some levels of capitalism, but also in how the development of technology itself is playing a crucial role in structuring and re-structuring their societies. Major technological developments change the way modern societies function, and while these changes have been taking place, we, in the Western part of the world, have not spent much time analysing these changes with the hermeneutical, phenomenological and other, more recent, scientific philosophies (cybersemiotics, for example) at our disposal. These approaches would give us the means to better understand what living in complex societies means, where human beings are directly affected by ever more complex interaction interfaces and digital systematisation in their daily lives. Considering the level of social change that has followed in the wake of these technological developments, it seems clear that the concept of communism is a theory of the past. We need a different theoretical approach and new conceptualisations in order to grasp the nature of current societies and where we are headed today.

In his more recent books, Klaus Schwab, the initiator and leader of the World Economic Forum and a proponent of what is called The Great Reset, does not support the idea of communism. On the contrary, his focus lies on deepening the tendencies we have already been experiencing for a long time in globalised societies.

Above all, Klaus Schwab advocates increased collaboration between multinational corporations and governments in what he calls ‘Stakeholder Capitalism’.

Furthermore, Schwab has linked the United Nations’ current approach to sustainability to the covid crisis. He has pointed out that the growth economy is not sustainable, and that the covid crisis will accentuate this imbalance. In his most recent book, Schwab suggests that collaboration between governments, NGO’s and big businesses should be strengthened, because these relations must become the source of solutions to the complex problems of global society, more specifically the climate crisis, the reset of the financial system, and the ongoing establishment of so-called ‘smart cities’. These concepts do not share much with a communist way of thought, since the capacity to reset and govern societies and smart cities does not lie with the state. To Klaus Schwab, relations between states and corporations will be crucial to addressing current challenges.

According to Patrick Wood [1], however, current events demonstrate that the overall process of globalization, combined with technological developments, multinational conglomerates and special, made-to-measure trade agreements that protect the interests of big corporations, has grown beyond the control of nation states. Over time, technocratic ideologies have penetrated deeply into our basic institutions, becoming a crucial influence in practically all areas of the societies in modern nation states. According to Wood, during its historical development, the ideology of technocracy became of strategic interest to particularly influential individuals during the period of the Second World War. Wood particularly emphasises the influence of the Trilateral Commission, a Think Tank founded by David Rockefeller in 1973, which counted Zbigniew Brzezinski and later Gro Harlem Brundtland among its members. The Trilateral Commission has had a profound influence on central policy-making institutions and has contributed significantly to the development of the UN’s Agenda 21 and the 17 Sustainable Development Goals that are now being implemented in nations all over the world. According to Wood, The Trilateral Commission had a particular interest in meeting the world’s most pressing challenges with an economic mindset, using engineering and technical-instrumental means. In its origins, the Trilateral Commission was shaped far more by economical than political considerations; its members have had a powerful influence on politics, education, research and economy. As a family, the Rockefellers have had a great influence on both the oil and the medical industries, shaping medical education and the conditions under which the medical industry has developed. In addition to this, Rockefeller became involved in the green sustainability movement very early on (Jakob Nordangaard).

Let us now delve deeper into the nature of technocracy and how it is to be understood.

Technocracy

For the purposes of this article, technocracy must be understood as a movement or philosophy that shapes both thought and action. As a movement, it has penetrated central social institutions both nationally and globally. It is a strategic ideology that masquerades as a call for action. From the beginning, the ideology of technocracy has been supported by some of the most influential people and families in the world, both financially and intellectually. Technocracy should not be understood as a broad movement representing the people, nor as a political movement. Rather, it is an ideology that is anchored firmly to technological development and is permeated by economic thinking. It is intrinsically linked to the idea of ‘scientific management’, an idea that allowed science and the development of industries move forward hand in hand with a focus on structure, efficiency and mass production as central pillars. It is crucial to understand that this movement has been able to penetrate and influence central institutions of power, such as the United Nations, the WHO and the WTO. Influential individuals, families and corporations have gained strategic avenues of influence and continue to do so today, partly because technology, in itself, has a potential for exponential growth. The coupling of technology and financial power has allowed specific individuals, families and corporations to gain power and capital for their own purposes. This potential has induced self-centred and power-hungry minds to rise to the fore, allowing them to dominate and take hold of society as a whole. Our current reality demands that we face this fact, learn to understand the ideology that is the foundation of our predicament and take a stance towards the technocratic takeover of the world.

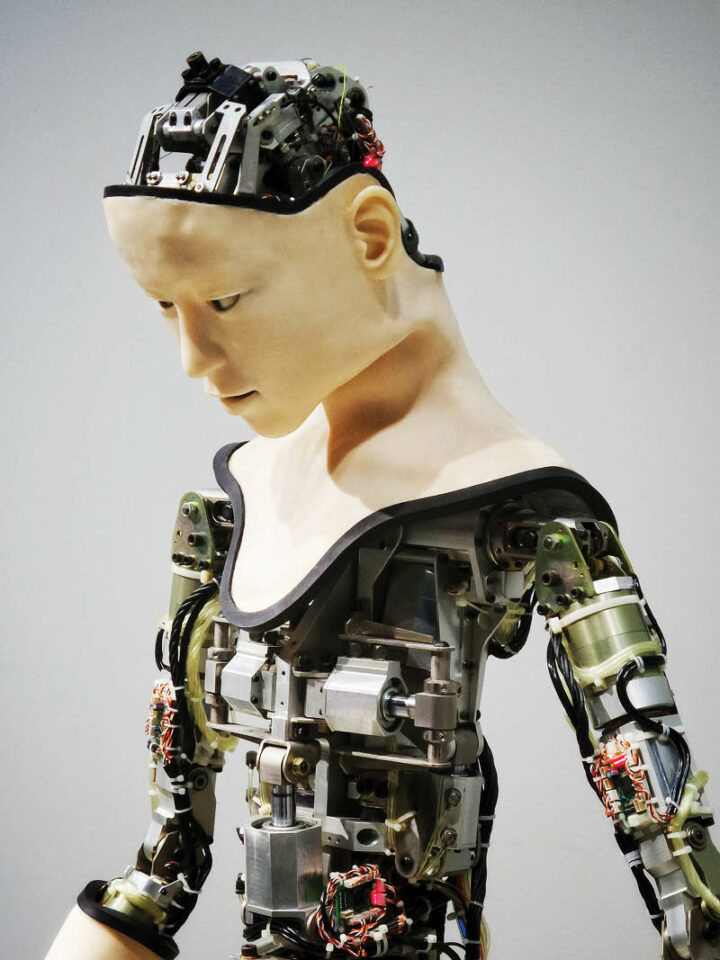

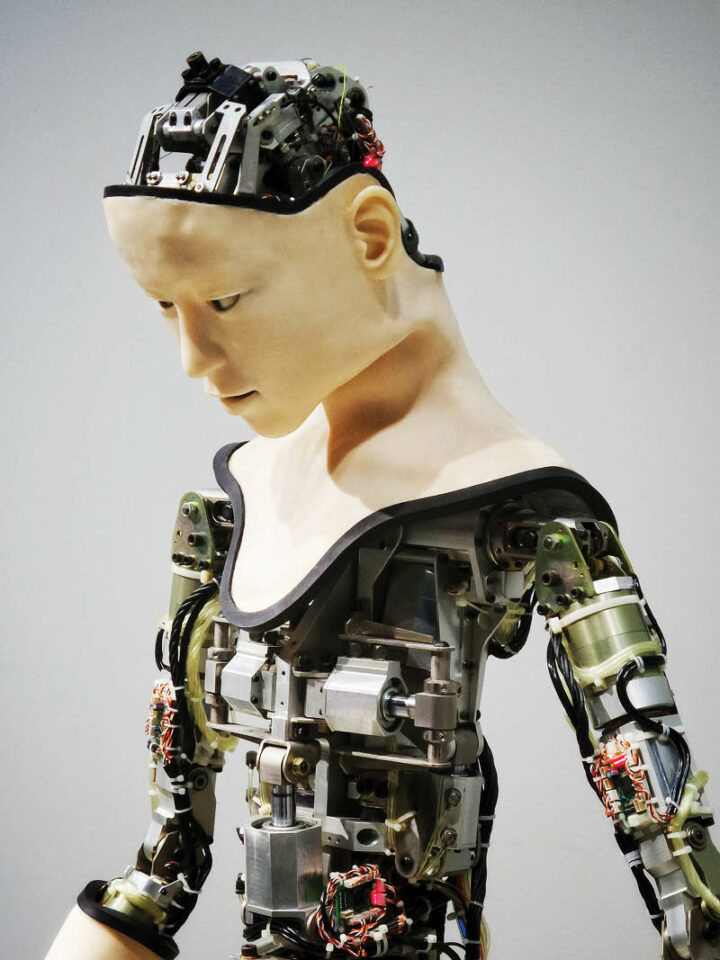

The technocratic movement can be called a ‘transhumanist ideology’.

Technocracy is a political system based on technical or expert rule. In this system, the power to make decisions lies with the experts, not the politicians. It is based on a belief that a technical approach, including the reliance on robots and AI, provides a more rational basis for decision-making. The question that remains is this: what is the place of humankind in such a system? Photo: Possessed photography på Unsplash.

This ideological approach to humankind has not, so far, gained a strong foothold in Western academia. The paradigm of transhumanism has been associated with eugenics, a school of thought that posits the right to determine which groups within society are ‘valuable’ and which are not and can therefore be excluded, an approach that many find repellent. It does not, therefore, have much popular support in academic institutions. This is also due to the negative aspects of eugenics, including its advocacy of euthanasia—which played an important role before and during the Second World War.

However, it seems as though transhumanism and eugenics have slipped in ‘through the back door’ in the wake of technological developments, especially with the ongoing trend towards ever more automatisation in society. As a result, technical, instrumental and managerial modes of thought have become dominant, giving rise to an undeclared technocratic approach that underlies decision-making in many modern nations and undermines a more humane self-understanding.

With the secretive mission Operation Paperclip, the American government brought more than 1,600 Nazi researchers (and their families) to the United States. In this way, knowledge, experience and research along with advanced military technology, aircraft technology, chemical and biological weapons were brought to the country. Knowingly, and concealed, that some of these researchers had been involved in experiments with Humans used as Guinea Pigs. Photo: media commons.

The broader public seems to have become infatuated by the overwhelming innovative dynamic inherent in technology, so that people have willingly subordinated themselves to it. This applies particularly to the fields of artificial intelligence, robotic technology, synthetic biology and bio-technology, on both micro and macro levels. Because of the strong potential for innovation that lies in technological development and its inherent complexity (for instance the construction of algorithms or web spiders), which most people cannot easily understand, a philosophy akin to transhumanism has been—at first indirectly, but now more overtly—gaining more and more influence. One could say that technological development, together with an exaggerated focus on digital systematisation and economic growth, has allowed transhumanism, largely unnoticed, to sneak in through the back door.

Over time, technocracy has become interwoven with supranational institutions such as UN, EU, WHO, WTO and other central world organisations.

During the past years, networks of supranational institutions, all of which subscribe to the Agenda 21/30, have entered binding agreements with each other concerning both what Schwab calls ‘The Fourth Industrial Revolution’ and The 17 Sustainable Development Goals. With regard to environmental issues, the shift from a broad perception of environmental issues to a narrow focus on CO2 has provided the basis for a continual technical or instrumental, managerial approach to the challenge, resulting mainly in increased taxes for citizens and CO2 quotas—as marketable products—that are presented as solutions to the crisis. The citizens end up paying the price while the people in power, not citizens of nation states, remain hidden from view and continue to profit from this arrangement. In other words, while both the sustainable development goals and the fourth industrial revolution are presented in favourable, utopian terms (for example, extinguishing all poverty on the globe by 2030), the entire movement follows the interests of the technocracy.

Overriding democracy as a tool for a global coup d’état

In order to understand the current situation and the influence exerted by supranational institutions as well as public-private partnerships between governments and private institutions or large companies, structures that order and influence the lives of ordinary people today, it must be realised that these structures are not the result of democratic processes. At the very least, there should be a discussion about the processes with which the European Union now shapes national law, both with regard to their democratic value and their value for individual nations. It is essential to understand, however, that although technocracy has become the main power and influence shaping the lives of citizens in all participating nations, there were never any democratic decisions taken on this issue. These structures of power reflect American and European interests and undoubtedly collaborate with key figures in China as well as other players. They make use of key persons strategically placed at transnational levels with comprehensive effects on individual states—without the people having any say at all in the decisions being made.

Globalization as a process has, in the end, shown itself to be stronger and more powerful than the internal processes and interests of national democracies. In fact, it seems as though democratic processes have become tools in the process of globalisation, rather than a goal.

In reality, therefore, power does not lie with democracies and the government officials supposedly representing the people, as many citizens of nation states still seem to believe.

On the basis of this understanding, we can look at the particularity of the Third World War as opposed to previous wars, where nations were fighting nations. This war is an expression of a different level of conflict between representatives of governments that are intertwined with the strategies and aims of the technocracy—above and beyond the interests and needs of the citizens of their nation states. In my view, therefore, this crisis goes beyond planning how to deal with a virus. The forces carrying forward the interests and aims of technocracy represent a broader group than those who organised the handling of the medical crisis. In fact, the medical crisis should be seen as merely the first phase of the war.

The pandemic as phase one of the war ensures the willing participation of governments in the overall plot, because the focus is on the medical sector—a sector that demands special competencies and knowledge in order to assess the situation. Furthermore, this sector is generally perceived as pre-eminently social in nature and it is assumed that it should therefore never be politicised. In the beginning, political restrictions such as lockdowns would have been unacceptable. However, when they were marketed as medical measures, people accepted them. We have been witnessing an extensive collaboration between states, the pharmaceutical industry and its sponsors, in the course of which the WHO and the vaccine industry gained more influence than the entire spectrum of democratic political processes. None of the measures taken accommodated the special interests of single nations—although the restructuring of the American economy and a re-positioning of the Dollar in the global financial markets may have played a significant role in the unfolding of events. As we attempt to understand the origins of the current war, we need to first determine what constitutes the greatest and most forceful power. This central power is the source giving rise to all further expressions of interests and affects everybody on the planet.

We must, however, continue asking the following question: How is it possible to execute such a comprehensive plan—in plain view, so to speak—while most of the population seems blind to what is happening? Why do people not understand that the goal of technocracy is full control? And what is the nature of a war that is carried out by hidden technocrats against the citizens of nation states all over the world?

To be continued.

Quellen:

[1] Patrick Wood (2018), Technocracy : The Hard Road to World Order. Coherent Publishing, LLC, ISBN10 0986373982, ISBN13 9780986373985.

Technocracy and the Third World War. An Essay Concerning the Question:

What Are the Most Effective Mechanisms of Power in the Today’s Global Society ? Part I

This text was first published on 19.04.2021 at <https://www.transformation20-25.net/> under the following URL: <https://www.transformation20-25.net/post/teknokratiet>. License: Kathrine Elizabeth Lorena Johansson © transformation20-25.net

Photo: Gerd Altmann by Pixabay.

Many people think that the current world crisis is a result of the effects of a virus. However, what we are experiencing today is far more comprehensive—it is about a fundamental reset of society on a global scale. Above all, the current crisis is a power struggle and has many characteristics of a war. But what kind of war? Who started it? Is it a battle between nations and, if so, what are they fighting for ?

First of all, we must understand that we have reached a new stage in the evolution of warfare. The initial stages of this war have shown that it is taking shape differently to former world wars.

War is about power and the control of resources. It is about using methods that overstep the rights of individuals in order to attain power.

Each world war has had different characteristics. In general, each war incorporates the knowledge, technology and communication technologies characteristic of its own historical period. Today’s war is thus different to former wars. Over time, there has been a continual move away from physical combat at close quarters to combat with a steadily expanding geographic range and ever more devastating weapons. World War I was characterised by new flight and bombing technologies, trench warfare and the use of chemical weapons (including trials with vaccines using field soldiers at the field hospitals in Germany). World War II led to a more advanced and industrialised war machine, strongly influenced by an ideology of ‘scientific management’ and was characterised by organized transportation, organized death camps, advanced (unethical) medical research and experimentation with the atom bomb in Japan.

Today’s war has shifted further away from the physically tangible dimension, into more virtual realms.

War has become less visible, but more universal in its reach. This war involves the whole world at one and the same time.

„Spyros Koukoulomatis Technocrat“ by Yannis Zannias Creative Commons.

The overall goal, however, remains the same: gaining power and control over populations and resources. In this article I attempt to outline the characteristics of the war we are presently experiencing and probe more deeply into the following question: How is it possible that so many nations and authorities seem to be following the same script, in spite of a very low level of scientific credibility and logical coherence in both the foundational explanations and strategies of action pursued by both Danish and foreign governments? To reach a greater understanding of the situation, we further ask: How do we determine the source of the power and resources that make such a global coup d’etat possible? In this article, I retain a special focus on the West and on technocracy per se.

Communism, liberalism or a whole new concept?

Many people have discussed the silent war we are experiencing and how it seems to be an attempt to drive modern nations into a kind of communism with the state gaining total power, enabling it to systemically control of the lives of citizens in a brutal and repressive way. In the past, we have seen variations of this dynamic in communist states in Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, or more harshly in North Korea and China. From a realistic point of view, both socialism (Karl Marx) and liberalism (John Locke, Adam Smith) represent outdated theories relating to a world that existed more than one hundred years ago. One must wonder whether countries that still adhere to a communist ideology, such as China today, may also be moving towards an entirely new condition—not only in the way the country integrates some levels of capitalism, but also in how the development of technology itself is playing a crucial role in structuring and re-structuring their societies. Major technological developments change the way modern societies function, and while these changes have been taking place, we, in the Western part of the world, have not spent much time analysing these changes with the hermeneutical, phenomenological and other, more recent, scientific philosophies (cybersemiotics, for example) at our disposal. These approaches would give us the means to better understand what living in complex societies means, where human beings are directly affected by ever more complex interaction interfaces and digital systematisation in their daily lives. Considering the level of social change that has followed in the wake of these technological developments, it seems clear that the concept of communism is a theory of the past. We need a different theoretical approach and new conceptualisations in order to grasp the nature of current societies and where we are headed today.

In his more recent books, Klaus Schwab, the initiator and leader of the World Economic Forum and a proponent of what is called The Great Reset, does not support the idea of communism. On the contrary, his focus lies on deepening the tendencies we have already been experiencing for a long time in globalised societies.

Above all, Klaus Schwab advocates increased collaboration between multinational corporations and governments in what he calls ‘Stakeholder Capitalism’.

Furthermore, Schwab has linked the United Nations’ current approach to sustainability to the covid crisis. He has pointed out that the growth economy is not sustainable, and that the covid crisis will accentuate this imbalance. In his most recent book, Schwab suggests that collaboration between governments, NGO’s and big businesses should be strengthened, because these relations must become the source of solutions to the complex problems of global society, more specifically the climate crisis, the reset of the financial system, and the ongoing establishment of so-called ‘smart cities’. These concepts do not share much with a communist way of thought, since the capacity to reset and govern societies and smart cities does not lie with the state. To Klaus Schwab, relations between states and corporations will be crucial to addressing current challenges.

According to Patrick Wood [1], however, current events demonstrate that the overall process of globalization, combined with technological developments, multinational conglomerates and special, made-to-measure trade agreements that protect the interests of big corporations, has grown beyond the control of nation states. Over time, technocratic ideologies have penetrated deeply into our basic institutions, becoming a crucial influence in practically all areas of the societies in modern nation states. According to Wood, during its historical development, the ideology of technocracy became of strategic interest to particularly influential individuals during the period of the Second World War. Wood particularly emphasises the influence of the Trilateral Commission, a Think Tank founded by David Rockefeller in 1973, which counted Zbigniew Brzezinski and later Gro Harlem Brundtland among its members. The Trilateral Commission has had a profound influence on central policy-making institutions and has contributed significantly to the development of the UN’s Agenda 21 and the 17 Sustainable Development Goals that are now being implemented in nations all over the world. According to Wood, The Trilateral Commission had a particular interest in meeting the world’s most pressing challenges with an economic mindset, using engineering and technical-instrumental means. In its origins, the Trilateral Commission was shaped far more by economical than political considerations; its members have had a powerful influence on politics, education, research and economy. As a family, the Rockefellers have had a great influence on both the oil and the medical industries, shaping medical education and the conditions under which the medical industry has developed. In addition to this, Rockefeller became involved in the green sustainability movement very early on (Jakob Nordangaard).

Let us now delve deeper into the nature of technocracy and how it is to be understood.

Technocracy

For the purposes of this article, technocracy must be understood as a movement or philosophy that shapes both thought and action. As a movement, it has penetrated central social institutions both nationally and globally. It is a strategic ideology that masquerades as a call for action. From the beginning, the ideology of technocracy has been supported by some of the most influential people and families in the world, both financially and intellectually. Technocracy should not be understood as a broad movement representing the people, nor as a political movement. Rather, it is an ideology that is anchored firmly to technological development and is permeated by economic thinking. It is intrinsically linked to the idea of ‘scientific management’, an idea that allowed science and the development of industries move forward hand in hand with a focus on structure, efficiency and mass production as central pillars. It is crucial to understand that this movement has been able to penetrate and influence central institutions of power, such as the United Nations, the WHO and the WTO. Influential individuals, families and corporations have gained strategic avenues of influence and continue to do so today, partly because technology, in itself, has a potential for exponential growth. The coupling of technology and financial power has allowed specific individuals, families and corporations to gain power and capital for their own purposes. This potential has induced self-centred and power-hungry minds to rise to the fore, allowing them to dominate and take hold of society as a whole. Our current reality demands that we face this fact, learn to understand the ideology that is the foundation of our predicament and take a stance towards the technocratic takeover of the world.

The technocratic movement can be called a ‘transhumanist ideology’.

Technocracy is a political system based on technical or expert rule. In this system, the power to make decisions lies with the experts, not the politicians. It is based on a belief that a technical approach, including the reliance on robots and AI, provides a more rational basis for decision-making. The question that remains is this: what is the place of humankind in such a system? Photo: Possessed photography på Unsplash.

This ideological approach to humankind has not, so far, gained a strong foothold in Western academia. The paradigm of transhumanism has been associated with eugenics, a school of thought that posits the right to determine which groups within society are ‘valuable’ and which are not and can therefore be excluded, an approach that many find repellent. It does not, therefore, have much popular support in academic institutions. This is also due to the negative aspects of eugenics, including its advocacy of euthanasia—which played an important role before and during the Second World War.

However, it seems as though transhumanism and eugenics have slipped in ‘through the back door’ in the wake of technological developments, especially with the ongoing trend towards ever more automatisation in society. As a result, technical, instrumental and managerial modes of thought have become dominant, giving rise to an undeclared technocratic approach that underlies decision-making in many modern nations and undermines a more humane self-understanding.

With the secretive mission Operation Paperclip, the American government brought more than 1,600 Nazi researchers (and their families) to the United States. In this way, knowledge, experience and research along with advanced military technology, aircraft technology, chemical and biological weapons were brought to the country. Knowingly, and concealed, that some of these researchers had been involved in experiments with Humans used as Guinea Pigs. Photo: media commons.

The broader public seems to have become infatuated by the overwhelming innovative dynamic inherent in technology, so that people have willingly subordinated themselves to it. This applies particularly to the fields of artificial intelligence, robotic technology, synthetic biology and bio-technology, on both micro and macro levels. Because of the strong potential for innovation that lies in technological development and its inherent complexity (for instance the construction of algorithms or web spiders), which most people cannot easily understand, a philosophy akin to transhumanism has been—at first indirectly, but now more overtly—gaining more and more influence. One could say that technological development, together with an exaggerated focus on digital systematisation and economic growth, has allowed transhumanism, largely unnoticed, to sneak in through the back door.

Over time, technocracy has become interwoven with supranational institutions such as UN, EU, WHO, WTO and other central world organisations.

During the past years, networks of supranational institutions, all of which subscribe to the Agenda 21/30, have entered binding agreements with each other concerning both what Schwab calls ‘The Fourth Industrial Revolution’ and The 17 Sustainable Development Goals. With regard to environmental issues, the shift from a broad perception of environmental issues to a narrow focus on CO2 has provided the basis for a continual technical or instrumental, managerial approach to the challenge, resulting mainly in increased taxes for citizens and CO2 quotas—as marketable products—that are presented as solutions to the crisis. The citizens end up paying the price while the people in power, not citizens of nation states, remain hidden from view and continue to profit from this arrangement. In other words, while both the sustainable development goals and the fourth industrial revolution are presented in favourable, utopian terms (for example, extinguishing all poverty on the globe by 2030), the entire movement follows the interests of the technocracy.

Overriding democracy as a tool for a global coup d’état

In order to understand the current situation and the influence exerted by supranational institutions as well as public-private partnerships between governments and private institutions or large companies, structures that order and influence the lives of ordinary people today, it must be realised that these structures are not the result of democratic processes. At the very least, there should be a discussion about the processes with which the European Union now shapes national law, both with regard to their democratic value and their value for individual nations. It is essential to understand, however, that although technocracy has become the main power and influence shaping the lives of citizens in all participating nations, there were never any democratic decisions taken on this issue. These structures of power reflect American and European interests and undoubtedly collaborate with key figures in China as well as other players. They make use of key persons strategically placed at transnational levels with comprehensive effects on individual states—without the people having any say at all in the decisions being made.

Globalization as a process has, in the end, shown itself to be stronger and more powerful than the internal processes and interests of national democracies. In fact, it seems as though democratic processes have become tools in the process of globalisation, rather than a goal.

In reality, therefore, power does not lie with democracies and the government officials supposedly representing the people, as many citizens of nation states still seem to believe.

On the basis of this understanding, we can look at the particularity of the Third World War as opposed to previous wars, where nations were fighting nations. This war is an expression of a different level of conflict between representatives of governments that are intertwined with the strategies and aims of the technocracy—above and beyond the interests and needs of the citizens of their nation states. In my view, therefore, this crisis goes beyond planning how to deal with a virus. The forces carrying forward the interests and aims of technocracy represent a broader group than those who organised the handling of the medical crisis. In fact, the medical crisis should be seen as merely the first phase of the war.

The pandemic as phase one of the war ensures the willing participation of governments in the overall plot, because the focus is on the medical sector—a sector that demands special competencies and knowledge in order to assess the situation. Furthermore, this sector is generally perceived as pre-eminently social in nature and it is assumed that it should therefore never be politicised. In the beginning, political restrictions such as lockdowns would have been unacceptable. However, when they were marketed as medical measures, people accepted them. We have been witnessing an extensive collaboration between states, the pharmaceutical industry and its sponsors, in the course of which the WHO and the vaccine industry gained more influence than the entire spectrum of democratic political processes. None of the measures taken accommodated the special interests of single nations—although the restructuring of the American economy and a re-positioning of the Dollar in the global financial markets may have played a significant role in the unfolding of events. As we attempt to understand the origins of the current war, we need to first determine what constitutes the greatest and most forceful power. This central power is the source giving rise to all further expressions of interests and affects everybody on the planet.

We must, however, continue asking the following question: How is it possible to execute such a comprehensive plan—in plain view, so to speak—while most of the population seems blind to what is happening? Why do people not understand that the goal of technocracy is full control? And what is the nature of a war that is carried out by hidden technocrats against the citizens of nation states all over the world?

To be continued.

Quellen:

[1] Patrick Wood (2018), Technocracy : The Hard Road to World Order. Coherent Publishing, LLC, ISBN10 0986373982, ISBN13 9780986373985.